Mecca of the Mind

Raquel Ukeles

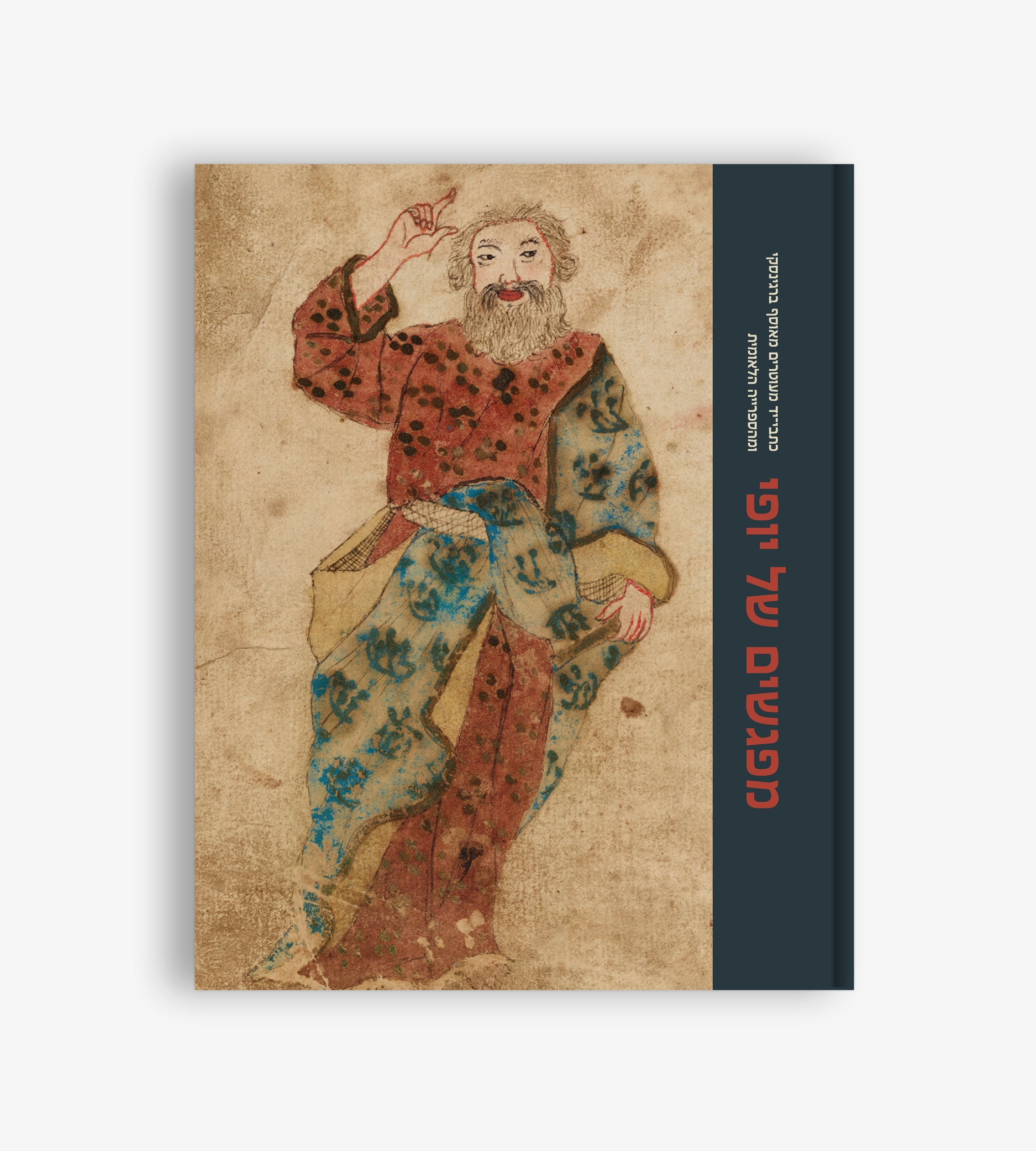

One of the most popular manuscripts in the premodern Muslim world was rarely produced in the Arab Middle East. Rather, thousands of handwritten copies of the prayer book, Signs of Benevolent Deeds (Dala’il al-khayrat), were copied in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and Central and South Asia.

The prayer book was written by Muhammad al-Jazuli (1404–65), one of the most revered Muslim Sufi mystics of medieval Morocco. Al-Jazuli developed a Sufi order centered on intensive spiritual love and devotion to the Prophet Muhammad. His prayer book includes prayers on behalf of the Prophet as well as spiritual meditations.

The immense popularity of this collection of prayers is often ascribed to two iconic illustrations found in most copies. Early North African manuscripts included two images from Medina: the Prophet’s burial chamber and his pulpit (minbar) and prayer niche (mihrab). These highly symbolic illustrations conform to the text’s focus on the Prophet and are found near the author’s reference to the famous Prophetic hadith: “Between my grave and my pulpit is one of the gardens of Paradise.” Later manuscript copies, especially from the Ottoman Empire and eastward, include a different set of two images. On the left, the Prophet’s mosque and burial chamber have been consolidated in one illustration, while on the right is an illustration of the Ka‘ba pilgrimage site in Mecca. Thus, the exclusive focus on the Prophet gave way to lavish double-sided illustrations of both Medina and Mecca.

These manuscripts highlight the cross-fertilization of North African Sufi prayers for the Prophet with Ottoman iconography of the sacred sites of Mecca and Medina. Following their sixteenth-century conquest of the Arabian Peninsula, the Ottoman sultans cultivated their reputation as guardians of the sacred pilgrimage sites and disseminated visual imagery of the Hajj pilgrimage sites throughout their empire.

The double imagery of Mecca and Medina was, in addition, a powerful visual representation of the first pillar of Islam: the testament of faith in the oneness of God and Muhammad as God’s messenger. The Ka‘ba at Mecca functions as the symbol of God on earth, while the mosque in Medina is the symbol of the beloved Prophet Muhammad. Together, the images offered a potent visual icon of Islam and its sacred sites for Muslims who aspired to go on pilgrimage and for those who could only dream of it.