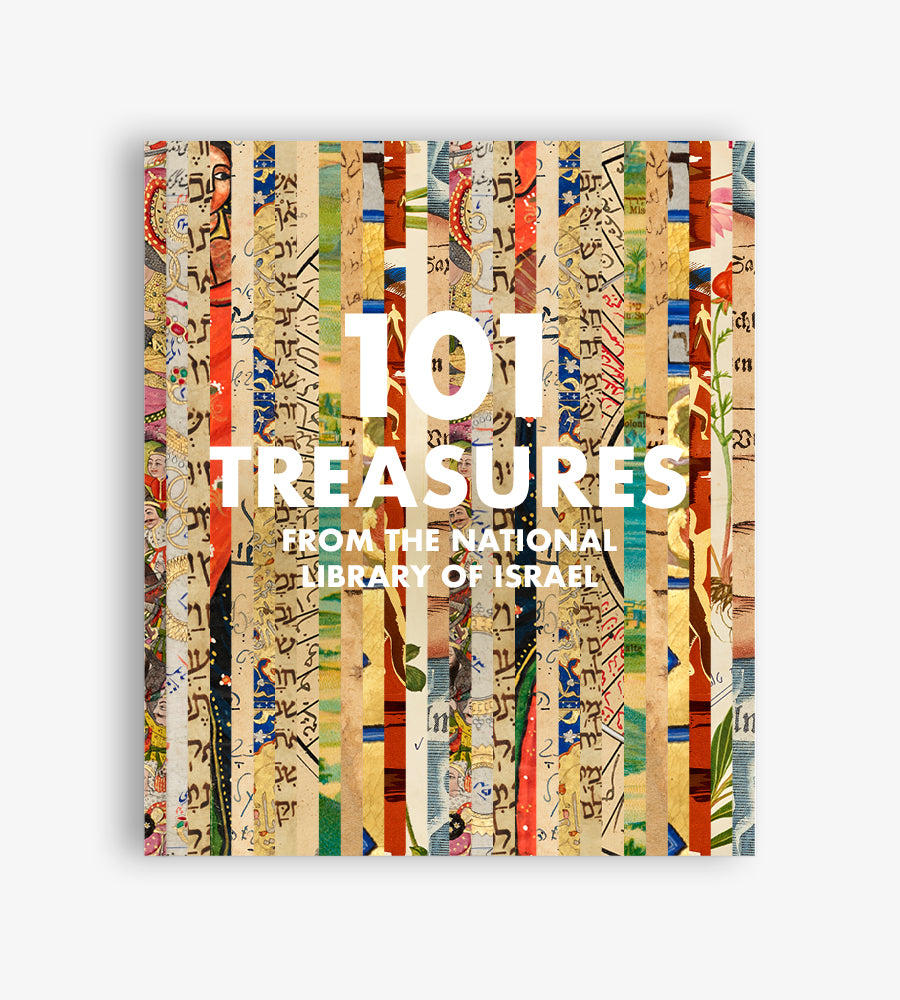

A Messiah in Real Time

Avriel Bar-Levav

In 1648, when Sabbatai Zevi (1626–76) first claimed to be the Jewish messiah, he was largely dismissed and disregarded. This changed in 1665 when he met Nathan of Gaza, who claimed to have foreseen his arrival and encouraged Sabbatai Zevi to accept the role of the Messiah. Nathan sent letters heralding the messianic age to Jewish communities all over the world, engendering an international movement of believers in Sabbatai Zevi. Testimonies from that period speak to the dramatic religious fervor that swept across Europe in response to the messianic hope.

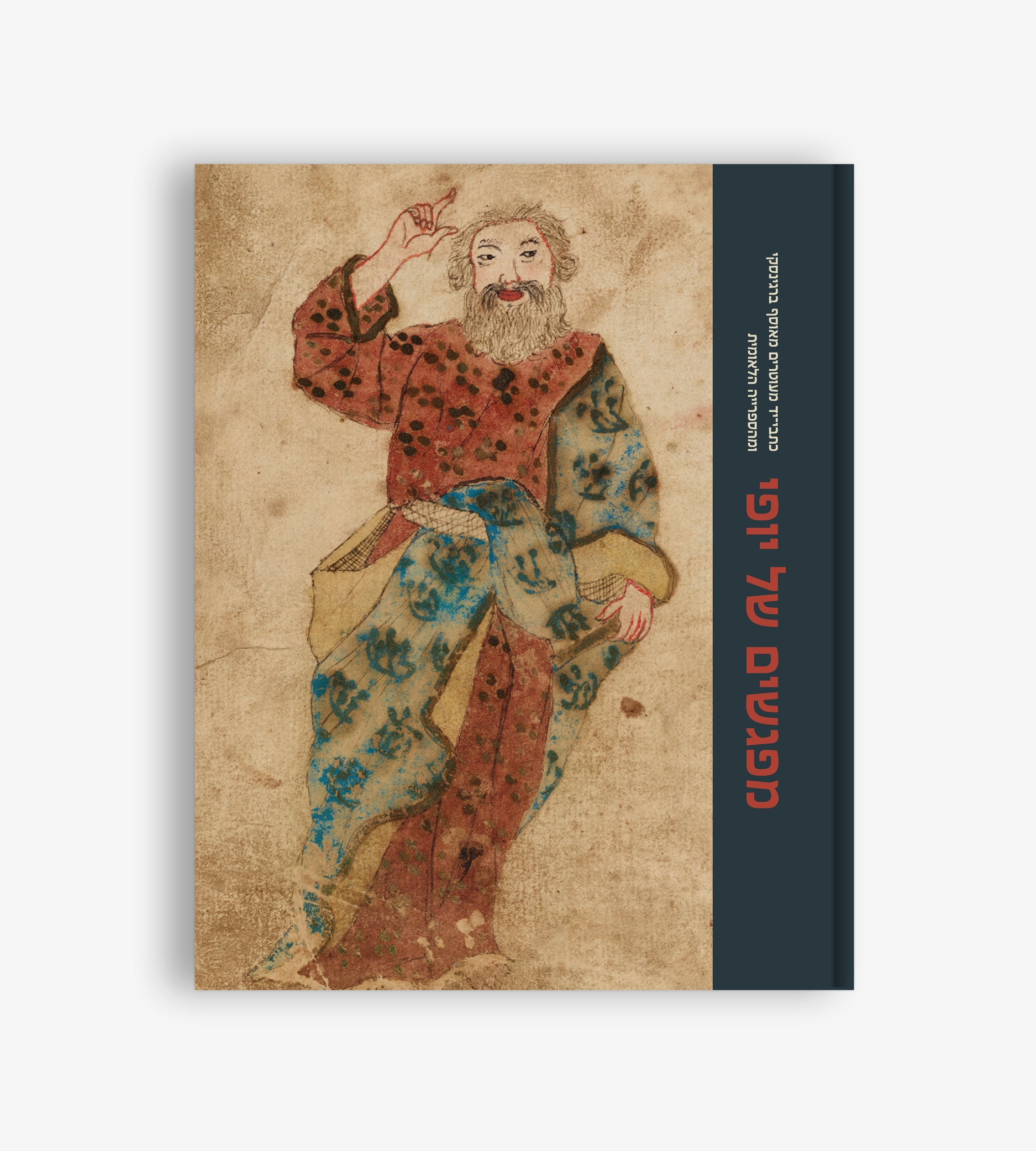

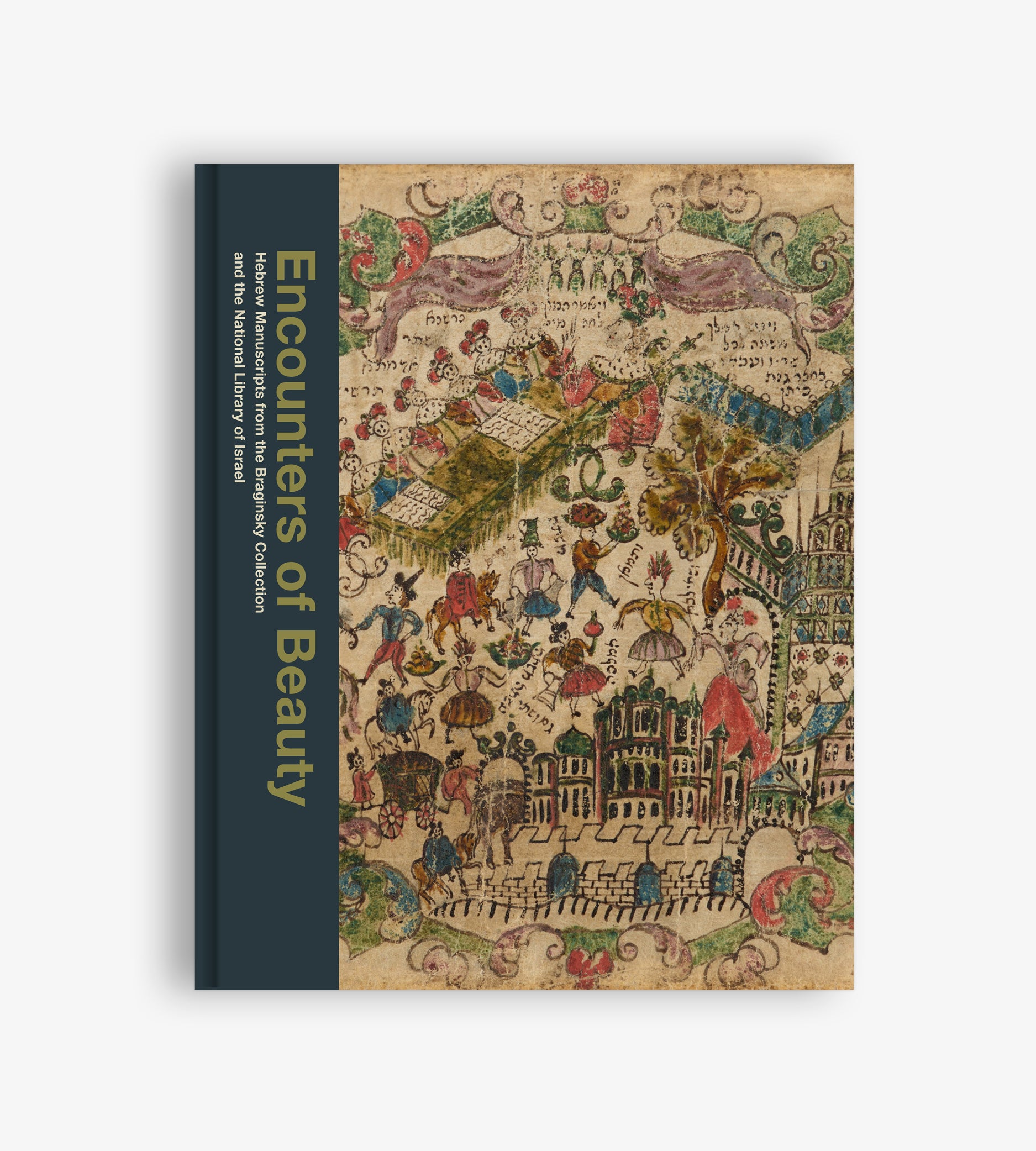

Sabbatai Zevi’s messianism evoked enthusiasm among Jews and interest among Muslims and Christians. In seventeenth-century Europe, world news was sometimes printed on broadsheets that were hung in public places around the city as a kind of proto-newspaper. Those who were not fully literate could look at the illustrations and try to make out the headlines in the margins. Broadsheets were useful in spreading information, and, as such, they were portents of some of the major transformations of the modern age as well as testimonies of older existing sentiments.

This broadsheet features the portraits of Sabbatai Zevi and Nathan of Gaza, likely drawn from imagination, and a text about them in Dutch. It was printed in Amsterdam in 1666, presumably by a Dutch Christian printer, and demonstrates the interest of Dutch Christian readers in developments on the Jewish street.

Just a few months later, Sabbatai Zevi converted to Islam due to pressure from the Ottoman sultanate. This shocking act weakened the messianic fervor, since a true Jewish messiah would never have converted to Islam. However, the ripple effects of Sabbatai Zevi’s transnational messianic movement would be felt in Jewish thought, culture, and politics for the next few centuries.