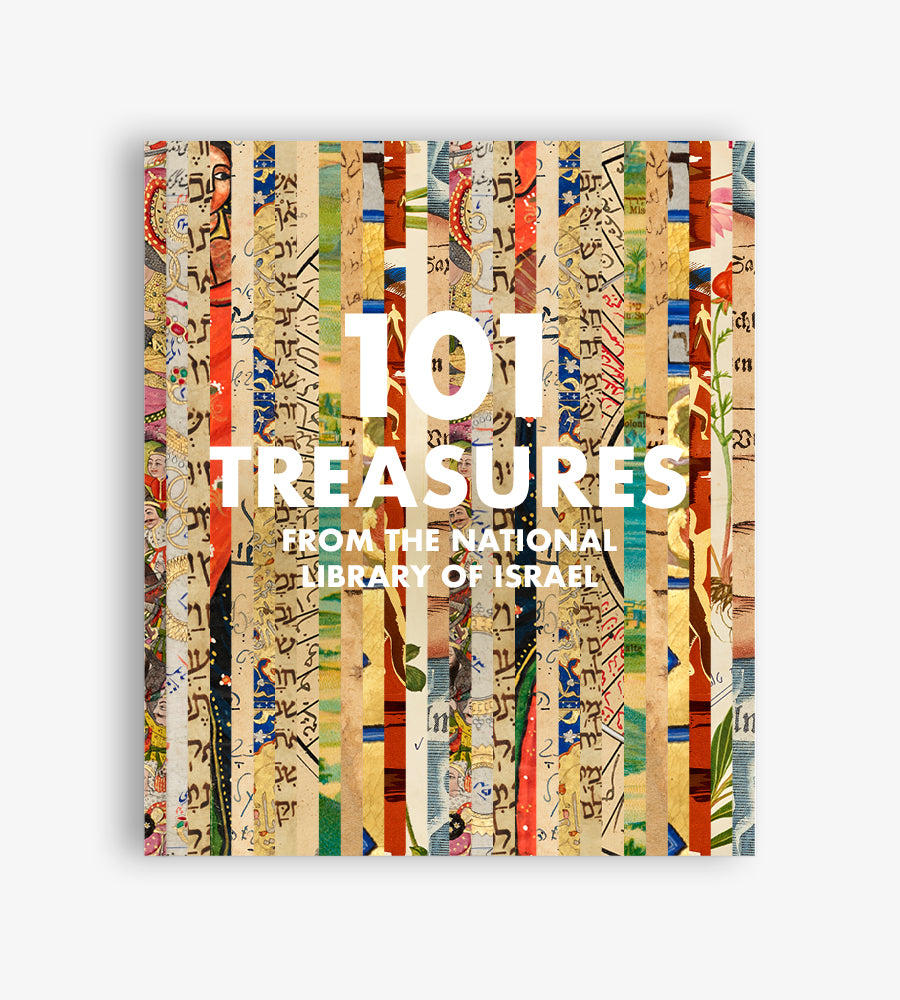

Exodus Before Expulsion

Yoel Finkelman

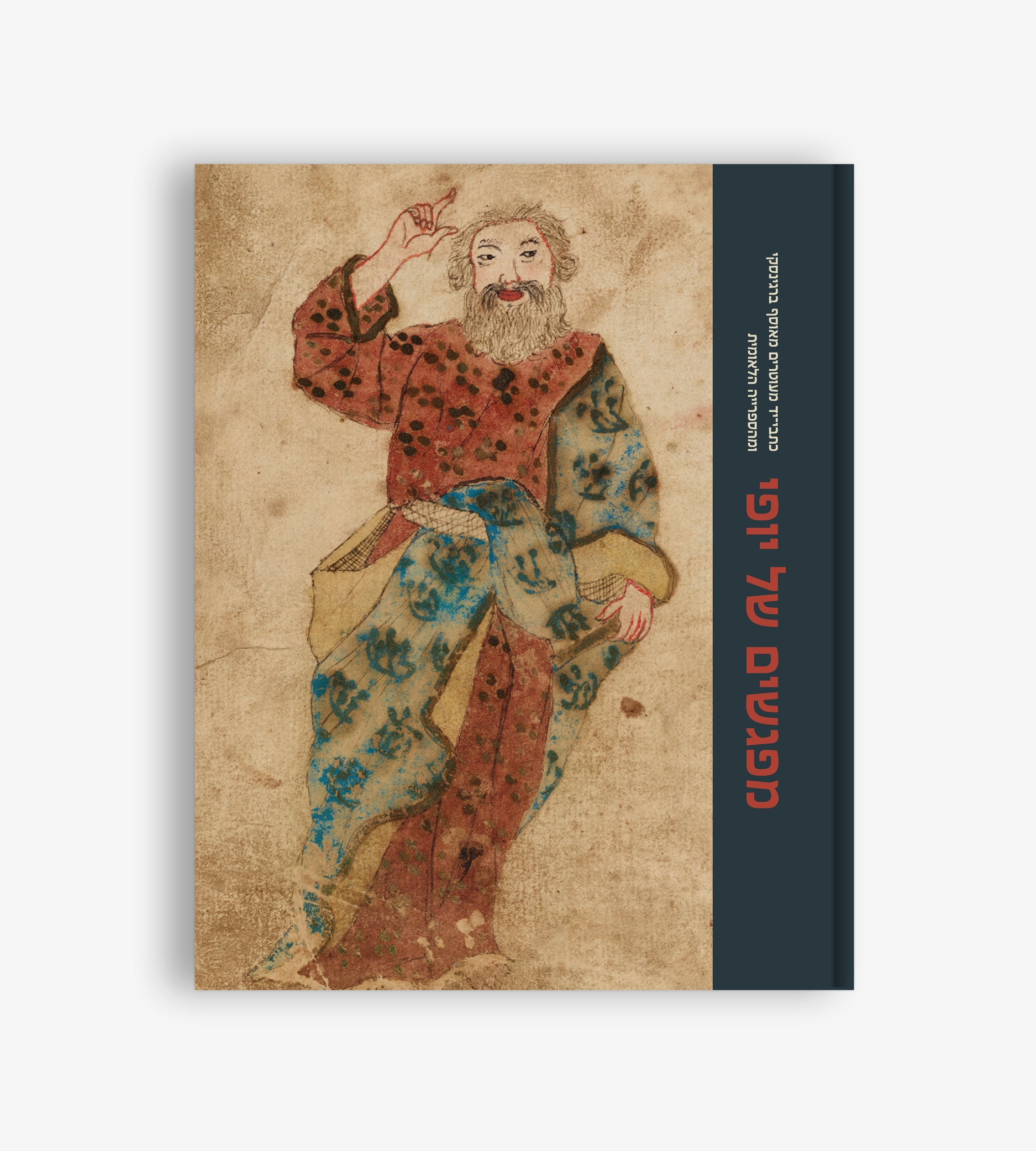

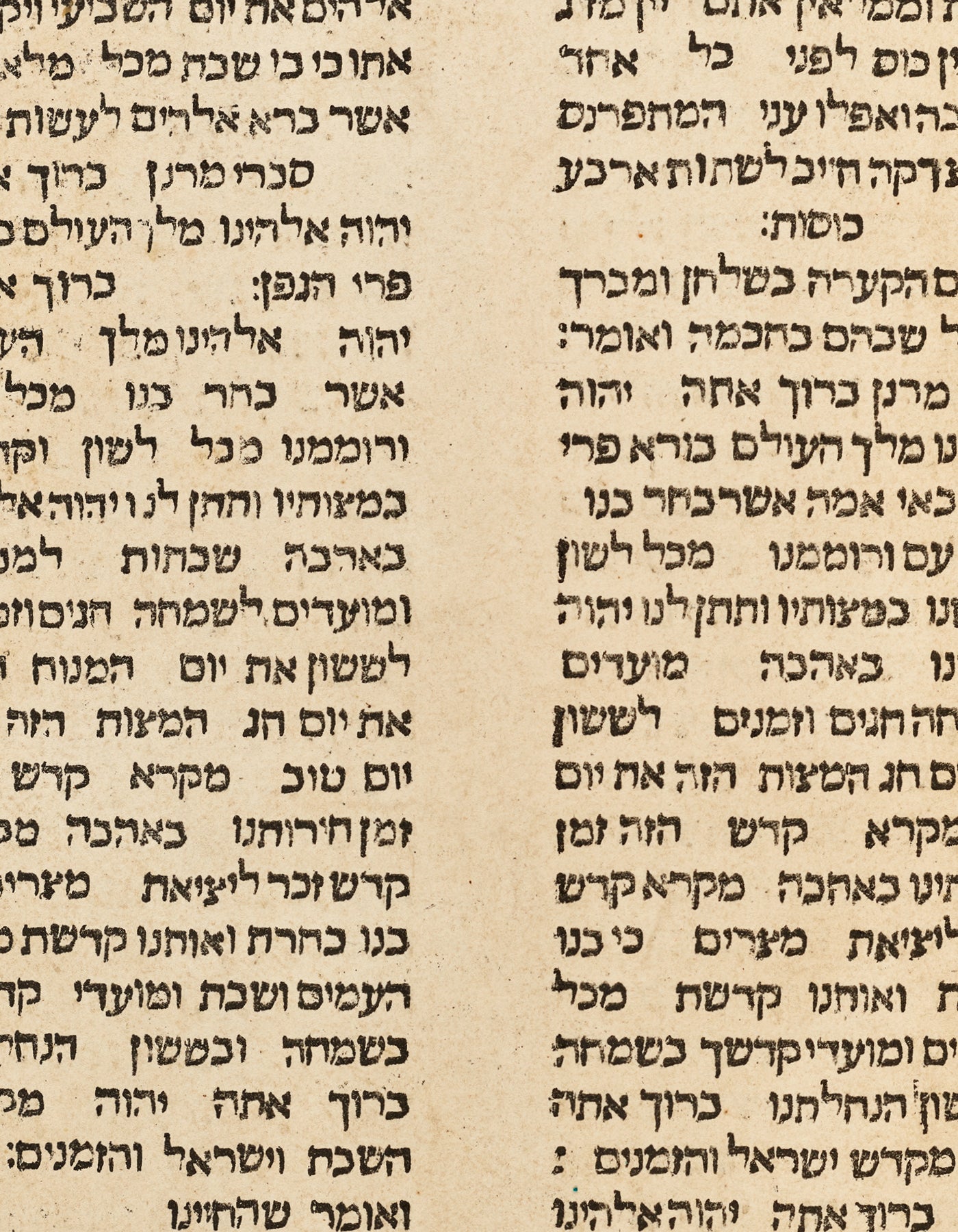

As printing spread throughout Europe in the second half of the fifteenth century, Jews in the Iberian Peninsula opened some of the first presses in the region. Printing was an expensive and risky endeavor, but Solomon ben Moses Alkabetz a pioneering printer in Guadalajara, Spain, realized that printing could benefit not only scholars but also Jews celebrating the holidays. A Passover Haggadah, he discerned, could serve as a profitable addition to his inventory. Sometime between 1480 and 1482 — just a few years before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain — he produced the first-ever printed Haggadah: a simple edition in two columns containing the traditional text with brief instructions but no commentary. The copy in the National Library is the only known extant copy.

This cutting-edge business decision launched an industry. Over 8,000 different editions of the traditional Haggadah have been published over the centuries — more than any other text in the history of Judaism. Some of this popularity stems from the fact that families would read the Passover liturgy in their own homes and use the text to spur a discussion of the lessons of the holiday. Each generation has endeavored to translate the text into its vernacular and make the story of the Exodus relevant to contemporary concerns, prompting editions in multiple languages with a range of commentaries and illustrations. The holiday’s focus on educating children has also stimulated publishers and authors to mediate the ancient text for young people and thus encourage discussion around the Passover table. Today, the National Library holds the world’s largest collection of Passover Haggadot.