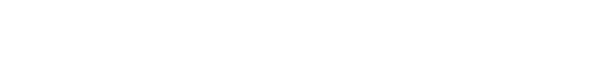

A Moment of Reform

Yael Levi

Liturgical changes are often signs of seismic shifts in religious beliefs and identities. A shorter service, the addition of prayers in the German language, and the removal of some references to sacrifices in this early Reform siddur of 1819 were portents of more radical changes in later Reform liturgy.

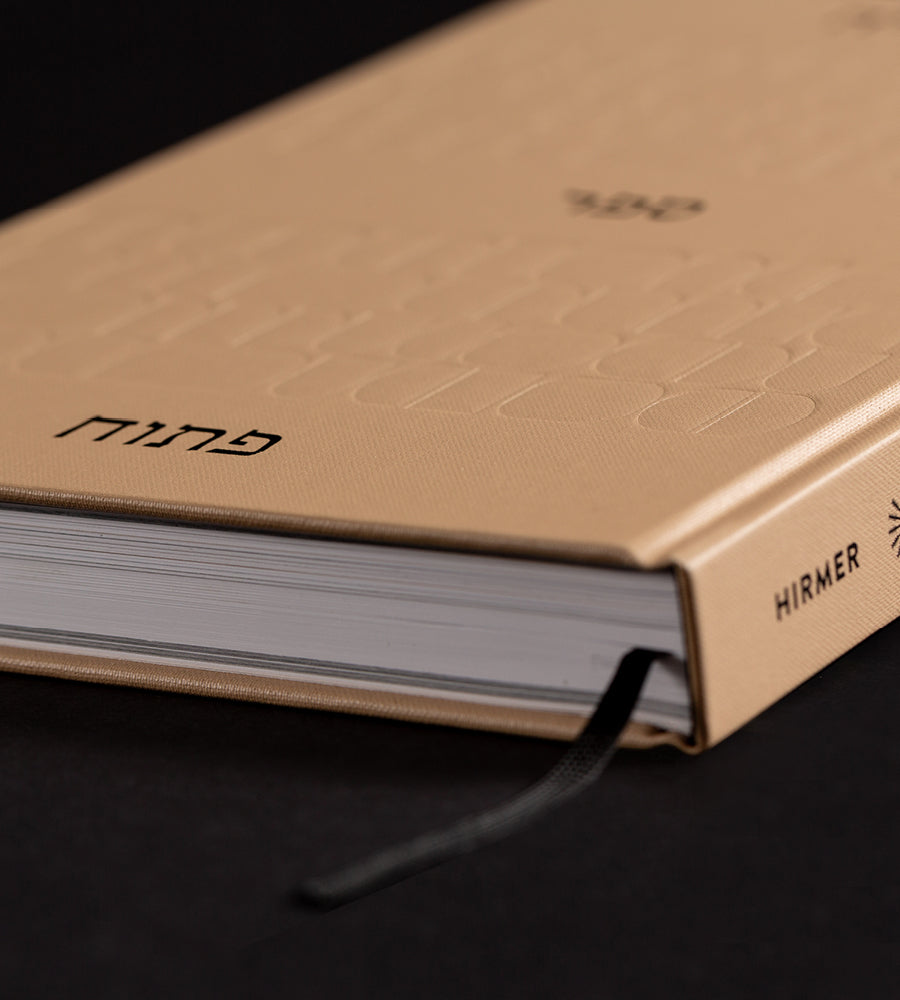

In October 1818, the Hamburg Temple was inaugurated as the first permanent Reform synagogue. A year later, Seckel Isaac Fränkel and Meyer Israel Bresselau published the first Reform siddur in Hebrew and German, Ordnung der öffentlichen Andacht für die Sabbath-und Festtage des ganzen Jahres (Order of Public Prayer for the Sabbath and Festival Days Throughout the Year).

Early Reform prayer books maintained significant continuity with older prayer books but also incorporated the values and aesthetics of the Haskalah — the German Jewish Enlightenment. Read from left to right, with the Hebrew above the line and a German translation below it, the siddur aimed to create an accessible text, appeal to aesthetic sentiment, and find a new balance between European acculturation and Jewish distinctiveness. As knowledge of Yiddish and Hebrew declined, German translation was needed to provide Jews access to the prayers.

While the liturgy of this prayer book is quite similar to that of traditional siddurim, later Reform prayer books made more significant changes, including omitting some sections of the prayers — such as the Mussaf service — and the omission or weakening of concepts such as angelology, the return to Zion, particularism, and sacrifices. This first Reform prayer book and its successors serve as a microcosm of the history of the movement, embodying through liturgy the quest to maintain Jewish heritage in a German cultural environment and a rapidly changing modern world.