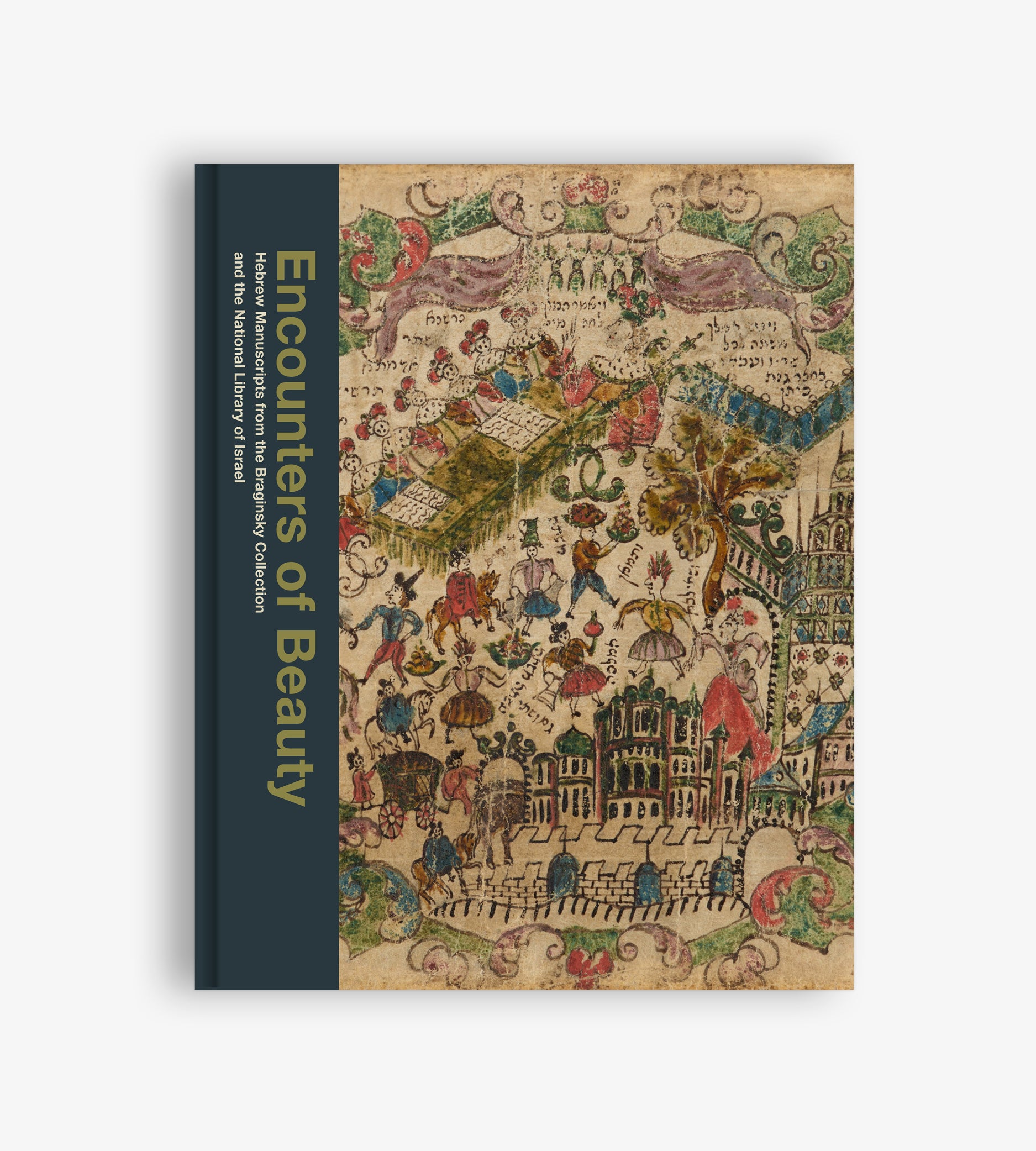

Beauty and Prayer

Stefan Litt

A visit to the old cities of Flanders, such as Bruges and Ghent, still gives an indication of the region’s role in world trade in the late Middle Ages. A successful textile industry and numerous merchants with business contacts throughout all of Europe made the southern Netherlands a hub of early international trade. Business and prosperity soon created a well-educated Christian economic elite with a fondness for luxury goods.

It was thus not by chance that more and more private workshops started producing books for stock and distribution in the southern Netherlands and northern France in the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Among their products were richly illuminated Christian prayer books (Horae or Books of Hours). Often these small and precious manuscript books were the perfect match for their wealthy clients, who, despite their fairly secular lifestyles, were still devoted to Christian religion and prayer.

Books of Hours usually contained common texts alongside psalms, hymns, and other parts of the Holy Scriptures. These texts were prayers that lay people – often women – would recite privately seven times a day at specific hours, as mandated by Western Christian tradition. In doing so, they were unintentionally adapting the older Jewish habit of praying three times a day. The inclusion of artful miniatures depicting scenes from the Passion of Jesus Christ and the lives of Christian saints made these books extremely attractive. These masterful illustrations, interspaced between the prayers, offered the books’ owners another, presumably welcome, layer of contemplation. The invention of book printing with movable type heralded the end of these manuscripts’ heyday by the early sixteenth century.